In our series on local heroes, this time I want to talk about Hasuda Zenmei.

When you search for “Hasuda Zenmei“ on Google and check Wikipedia, you’ll learn about the extraordinary life of this individual.

Speaking of self-sacrifice, the ritual suicide of Yukio Mishima is widely known in modern times, but there is actually a deep connection between Yukio Mishima and Zenmei Hasuda.

In the preface of the book “Zenmei Hasuda and His Death” by jiro Odakane , it is written as follows:

“I first understood what he was so angry about. It was anger towards the intellectual class in Japan. Anger towards the greatest ‘internal enemy.’ It is astonishing how the character of Japanese intellectuals, both during wartime and now, has remained almost unchanged. Their cowardice, their sneers, their objectivism, their rootless grass-like collective sentiment, their dishonesty, their worship of power, their gestures of resistance, their self-righteousness, their inaction, their verbosity, their empty words…”

Source:Yukio Mishima, Preface (from jiro Odakane’s ” Zenmei Hasuda and His Death”)

Now, let’s explore the background behind the common “anger” shared by these two individuals.

Birthplace

Zenmei Hasuda was born on July 28, 1904 (Meiji 37) as the third son of Jizen Hasuda, a chief priest of Konrenji, a Jodo Shinshu Otani-ha temple in Ueki-cho, Kamoto District, Kumamoto Prefecture (present-day Kita Ward, Kumamoto City), and his mother Fuji.

Zenmei Hasuda Memorial Monument

In Ueki-cho, there is a place called Tabaruzaka, which was the site of a fierce battle during the Satsuma Rebellion. Here, you can find the “Zenmei Hasuda Memorial Monument”, with words of tribute from former friends engraved on the back.

abumida kitsuki jinja

“In Ueki-cho, there is a shrine called Tabaruzaka Kitsukijinja. hayashi oen, who held great respect for Tabaruzaka Kitsukijinja and Shinkai daijingu Shrine, was a mentor of the Kumamoto shinpuren. It appears that Zenmei Hasuda and the son of the priest of Tabaruzaka Kitsukijinja were close friends.”

“The shinpuren appears in Yukio Mishima’s epic novel ‘The Sea of Fertility: Runaway Horses,’ and it evokes a sense of something fateful, doesn’t it?”

“Bungei Bunka”

“Awakening to National Literature”

“After graduating from Kumamoto Prefectural Middle School, Zenmei Hasuda enrolled in Hiroshima Higher Normal School. There, he came under the strong influence of Dr. Saitō Kiyoe, a professor of national literature, and began to immerse himself in the spirit of classical works.”

“During his fourth year at the school, Zenmei Hasuda, who served as the representative committee member of the alumni magazine ‘Kōya’ in the school’s Fine Arts Department, met Shimizu Fumio, a second-year student (who was the oldest among them), as well as Kuriyama Riichi and Ikeda Tsutomu, who were first-year students.”

“The establishment of ‘Bungei Bunka'”

In April 1938 (Showa 13), Zenmei Hasuda, along with Shimizu Fumio, Kuriyama Riichi, and Ikeda Tsutomu, established the “Nihon Bungaku no Kai” (Japanese Literature Society) with the aim of “becoming gods themselves and revitalizing literature in Japan.” Additionally, in the same year in July, they launched the monthly journal of Japanese literature, “Bungei Bunka,” with Hasuda as the editor and nominal representative. They also held a four-day event called the “Nihon Bungaku Kōen” (Japanese Literature Symposium) in Koyasan from July 28th.

“Encounter with Yukio Mishima”

“The Forest in Full Bloom”

“In April of Showa 16 (1941), Yukio Mishima, who advanced to the 5th year of middle school (at the age of 16), completed ‘The Forest in Full Bloom‘ and sent the manuscript to his Japanese language teacher, Fumio Shimizu, requesting feedback.”

At that time, Fumio Shimizu said that he was deeply impressed, as if something dormant within him had been strongly awakened.

Furthermore, Fumio Shimizu shared it with his fellow members of the Japanese Romanticism-based national literature magazine “Bungei Bunka” (Zenmei Hasuda, Tsutomu Ikeda, and Riichi Kuriyama), and they all celebrated the emergence of a “genius” and swiftly decided to publish it in the same magazine.

Shimizu Fumio, who hails from the same hometown of Kumamoto, is the one who gave Yukio Mishima (pen name) his name.

By reading “The Forest in Full Bloom,” Zenmei Hasuda, the founder of “Bungei Bunka” magazine, came to know Yukio Mishima.

Here is a part of the summary of “The Forest in Full Bloom.”

“I” reminisce about the house where I was born. I reflect on the “silent agreement” that flows like a river from my grandmother, mother, father, and the ancestors I admire. It’s not about which part of the river is the river, but rather the eternal meaning of the river lies in its flow. Admiration dwells and hides in a certain place, but it is not dead. In my grandmother and mother, the river flows underground, while in my father, it became a babbling brook. As for “me,” I wonder what it will become if it doesn’t turn into a roaring river but rather something woven, like a sacred song of the gods.”

source:『The Forest in Full Bloom』

“It’s astonishing that he wrote it at the age of 16, but I’m also in awe of his portrayal of the ‘spirit of Japan’.”

literary debut

“The Forest in Full Bloom” was serialized in the September to December 1941 issue of “Bungei Bunka”.

In the first postscript of the magazine, Zenmei Hasuda highly praised the young author, saying, “This young writer is undoubtedly a child of Japan’s ancient history. Despite being much younger than us, their work is already that of a mature individual.”

“Shinpuren no Kokoro”

Yukio Mishima, under the influence of Yasuda Yojuro, Zenmei Hasuda, and Shizuo Ito among others from the Japanese Romantic School, continued to publish his poetry, novels, and essays in “Bungei Bunka” magazine.

In particular, he was deeply impressed by Zenmei Hasuda’s teachings on “Imperial Spirit,” “Yamato Spirit,” and the essence of “Grace and Elegance.”

in the November issue of 1942, Zenmei Hasuda published an article titled “The Spirit of Shinpuren Squadron” in which he provided a review of “The Spirit of Shinpuren Squadron” written by Tadashi Morimoto, who was a senior at Kumamoto Seiseikou (Kumamoto Prefectural High School) several years ahead of Hasuda. The book was published by Kokumin Hyōronsha.

After reading “The Spirit of Shinpuren Squadron” and other works by Tadashi Morimoto, Yukio Mishima, in later years, visited the birthplace of the Shinpuren Squadron, Kumamoto, in August 1966. During his visit, he had a meeting with Tadashi Morimoto, who had become a professor at Kumamoto University.

“Deployment to the Southern Front”

Zenmei Hasuda, on October 25, 1943 (Showa 18), received his second call-up and was assigned as a platoon leader in the 123rd Infantry Regiment. In November, he departed for the Southern Front.

Farewell party

On the evening of the conscription day, a farewell party was held by the members of “Bungei Bunka” literary magazine.

During that time, Zenmei Hasuda said to Yukio Mishima, “I entrust the future of Japan to you.”

On that night, Riichi Kuriyama recalls that Hasuda repeatedly became enraged, expressing his frustration by reciting the songs of Shinpuren Squadron, while shedding tears of passion, saying, “Those American bastards…”

“Warabiuta”

In Surabaya, Java Island, Indonesia, Zenmei Hasuda encountered Haruo Sato and entrusted him with a compiled version of his field diary called “Warabiuta.”

During this time, Zenmei Hasuda sent letters resembling farewell letters to his second son, Taiji, who was in the second grade of elementary school, and his youngest son, Aruo, who was three years younger.

“Shinji, you’re full of energy and such a mischievous kid. Let’s unite as three brothers and protect Mom. Even without Dad, strive to become a fine person. If we join forces, we can truly become strong. Just like the Forty-Seven Ronin formed groups of three in secret and fought together. Dad is doing well. There are many monkeys in the forest around our house. Sometimes pigs stroll around too. There’s also a big lizard about one meter long. But there are no hippos, which you like. Goodbye.”

Source:Zenmei Hasuda’s postcard addressed to Taiji and Aruo (dated August 26, 1944):

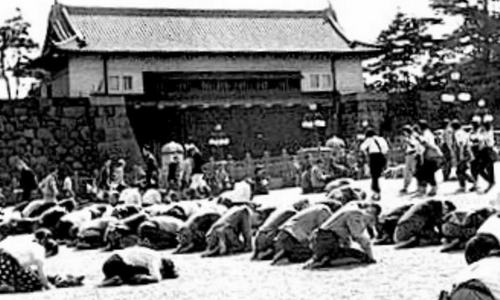

Defeat

On August 15, 1945, Japan’s surrender marked the end of the war.

Sudden change in superior officer

However, the undefeated and high-spirited Kumamoto infantry unit, fearing the possibility of the Emperor being held responsible for the war, were determined to resist until the last soldier and took independent action within the military to continue fighting.

In the midst of this, a secret plan led by young officers was underway, and Captain Torigoe was organizing a resistance force. Zenmei Hasuda was also designated as the commander of that resistance force.

Colonel Toyoma Nakajo, who sensed this unsettling development, gathered non-commissioned officers and above at the New Imperial Palace on the mountain within the headquarters premises to assert control over the formation of the resistance force. On August 18th, he conducted a flag farewell ceremony and delivered a message.

According to Captain Torigoe’s recollection, at this time, Colonel Nakajo “blamed the Emperor for the defeat, slandered the future of the Imperial Army, and preached the destruction of the Japanese spirit.”

Many young officers were outraged by Colonel Toyoma Nakajo’s drastic change and betrayal, which seemed contrary to his military persona.

Among them, Lieutenant Hasuda’s anger was intense. Immediately after the gathering, he collapsed to his knees, clutching the legs of Major Takaho Akioka, the battalion commander, with both arms, and cried out, “Major! I am filled with regret!”

Determination

Upon hearing Captain Nakajo’s address on August 18th, Zenmei Hasuda, driven by determination, decided to kill Nakajo himself and become a “guardian demon” in order to sacrifice his own life for the protection of the nation.

The following is an anecdote from when Lieutenant Torikoshi had a lunch meeting with four senior officers in his adjutant’s office.

During the lunch meeting, Captain Takagi took the side of Colonel Nakajo and displayed a dismissive attitude, saying that if you were to ask children who the most important person in Japan was, they would mention names like Roosevelt or Chiang Kai-shek, but no one would mention the Emperor.

In response to this, Hasuda vehemently objected, saying, “Such nonsense! As long as Japan continues to exist and the Japanese people endure, the Emperor is the highest authority. Without anyone teaching them, every Japanese child instinctively reveres the Emperor as the Supreme Being.”

“Tch, it’s no joke. We don’t even know if we’ll make it back alive. Instead of wasting time with pointless arguments like Colonel Nakajo said, shouldn’t we be seriously thinking about how to survive?” Captain Takagi retorted sharply.

“We must never forget the spirit of Japan, whether we make it back alive or return in death!” Zenmei raised his voice, his tone filled with intensity.

Source:odakane jiro「Zenmei Hasuda and His Death」

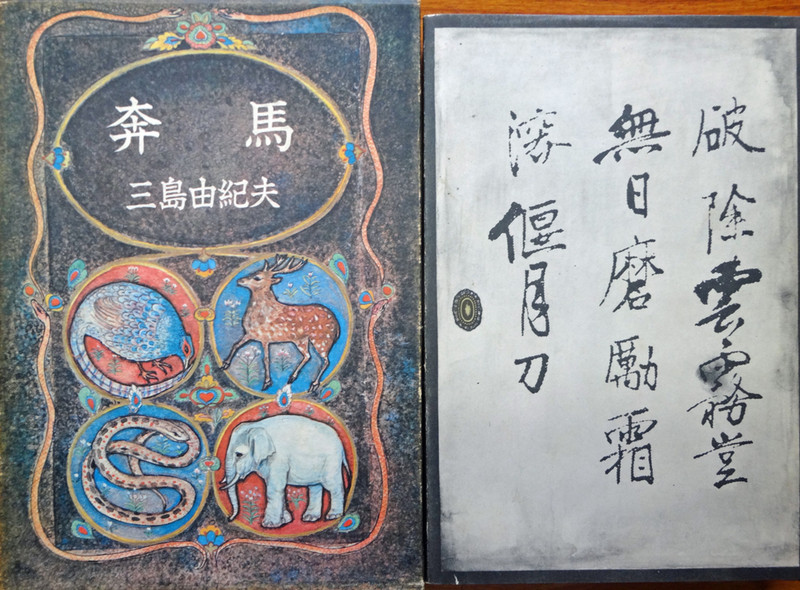

This reminds me of the concept of “purity” in Yukio Mishima’s epic novel “The Sea of Fertility: Runaway Horses,” volume 2.

Shooting and then committing self-disposal

On that day, Colonel Nakajo, accompanied by Lieutenant Tsukamoto carrying a box containing the regimental flag, walked out of the headquarters’ entrance.

And as Colonel Nakajo attempted to get into the waiting car, Zenmei Hasuda, who had been lying in wait in the blind spot outside the window of the adjutant’s office, suddenly leaped out from behind Corporal Kuroda, shouting “Traitor!” and fired two shots from his pistol, killing Colonel Nakajo.

Afterward, Zenmei Hasuda pressed the pistol against his temple and took his own life in a act of self-inflicted gunshot.

At that moment, when Zenmei Hasuda initially pulled the trigger, the gun misfired, providing him with a window of opportunity to reconsider his suicide. However, Sergeant Kuroda intentionally chose not to intervene and allowed the events to unfold as they did.

Zenmei Hasuda and Yukio Mishima

In June 1966, Yukio Mishima began his research for the second volume of his serialized novel, “Honba.”

To the places associated with the Shinpuren Squadron

Upon arriving in Kumamoto for the research, Mishima was greeted by Seishi Araki and others. He met with Zenmei Hasuda’s widow and Tadashi Morimoto, Hasuda’s senior, and conducted interviews at locations associated with the Shinpuren Squadron, such as Shinkai Daigongen Shrine and Sakurayama Shrine. Mishima also purchased a Japanese sword worth 100,000 yen.

Prior to this journey, Mishima wrote to Shizuo Shimizu, stating, “It is pathetic that people still believe in the theory proposed by Kamei Katsuichiro that the sacredness of the Emperor originates from Ito Hirobumi’s Constitution, and even Yamamoto Kenkichi believes it. It was because of this that I became interested in the Shinpuren Squadron. I have a premonition that there is something fundamentally essential in the Shinpuren Squadron.”

Zenmei Hasuda and His Death

As mentioned briefly at the beginning, in the preface of Jiro Kotakane’s book “Zenmei Hasuda and His Death,” the essence of Zenmei Hasuda’s “anger” is examined as follows.

I first came to understand what he was so angry about. It was anger towards the intellectuals of Japan, the greatest “internal enemy.” The fact that the character of Japanese intellectuals, both during wartime and in the present, has remained largely unchanged is astonishing. Their cowardice, their sneering, their objectivism, their rootless collective sentiment, their insincerity, their imperialistic tendencies, their gestures of resistance, their self-righteousness, their inaction, their verbosity, their empty promises… When these traits were adorned with hypocrisy during wartime, they unleashed a corruption that poisoned the essence of culture. Zenmei Hasuda observed all of this meticulously and, with the uncompromising kindness of his youth, he was consumed by indignation for the sake of a culture that had lost its way.

Source:Yukio Mishima, Preface (from jiro Odakane’s ” Zenmei Hasuda and His Death”)

This issue remains exactly the same in the present day, if not worse…

Summary

What did you think? Do you resonate with Mishima’s analysis in the preface of “Zenmei Hasuda and His Death”?

As you may know, Tabaruzaka, the hometown of Zenmei Hasuda, was also the site of fierce battles between the Satsuma forces led by Takamori Saigo and the Imperial forces.

Below are the photos taken during my revisit for the blog post.

The original manuscript of Yukio Mishima’s handwritten “Hanazakari no Mori,” which was previously missing, was discovered in September 2016 at the residence of the Hasuda family in Kumamoto City. The Hasuda family is the home of Zenmei Hasuda’s eldest son, Shoichi.

This further reveals the profound relationship between Yukio Mishima and Zenmei Hasuda.

Finally, the inscription on the “Zenmei Hasuda Literary Monument” located in Tabaruzaka concludes with the following words:

“You were inherently sincere and earnest, showing deep affection towards your close relatives and friends, sparing no effort in your pursuit of learning. Your purity of character and elevated scholarly demeanor can only be described as exemplary. We now lament your untimely passing and pray for your eternal protection over our homeland. In remembrance of our former friendship, we have erected this monument.”